این نیز بگذرد

(This Too Shall Pass)

این نیز بگذرد

(This Too Shall Pass)

این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) is an attempt to address the desperate situation of migrants in Europe today while trying to untangle the problems of representation within photography. Consisting of three works, این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) revolves around a two-meter-wide enlargement of a screenshot from an online roleplaying game which might at first sight appear unreadable. As the surrounding works gradually reveal the image to depict the very moment which made it possible for Yashar Maghsoudi to escape from Iran, the image proves to be the most accurate representation of Yashar's complex story of migration and escape – in a form and a language which has to be read through Yashar’s perspective in order to be comprehended.

In the image, Yashar plays as the World of Warcraft Blood Elf Paladin "Nighetboy". 13 years old, forming a group with other players and traveling for hours across all the virtual borders in world of the game, Yashar had finally been able to make it into the heart of the capital city of the opposing nation. While one of the most difficult achievements in the game, Yashar couldn’t realize the full significance of this until two years later. In real life, Yashar was living in the city Bandar-e Anzali in Iran when he was suddenly accused of trying to convert from Islam. Persecuted by the Islamic religious police and forced to escape the country, Yashar was able to sell his virtual character in order to pay for his real escape, most likely saving his life. Consequently, by participating in a virtual conflict and managing to make it across the borders of a fictional world, it became possible for Yashar to cross the very real borders of Iran and Europe, and finally make it to Sweden.

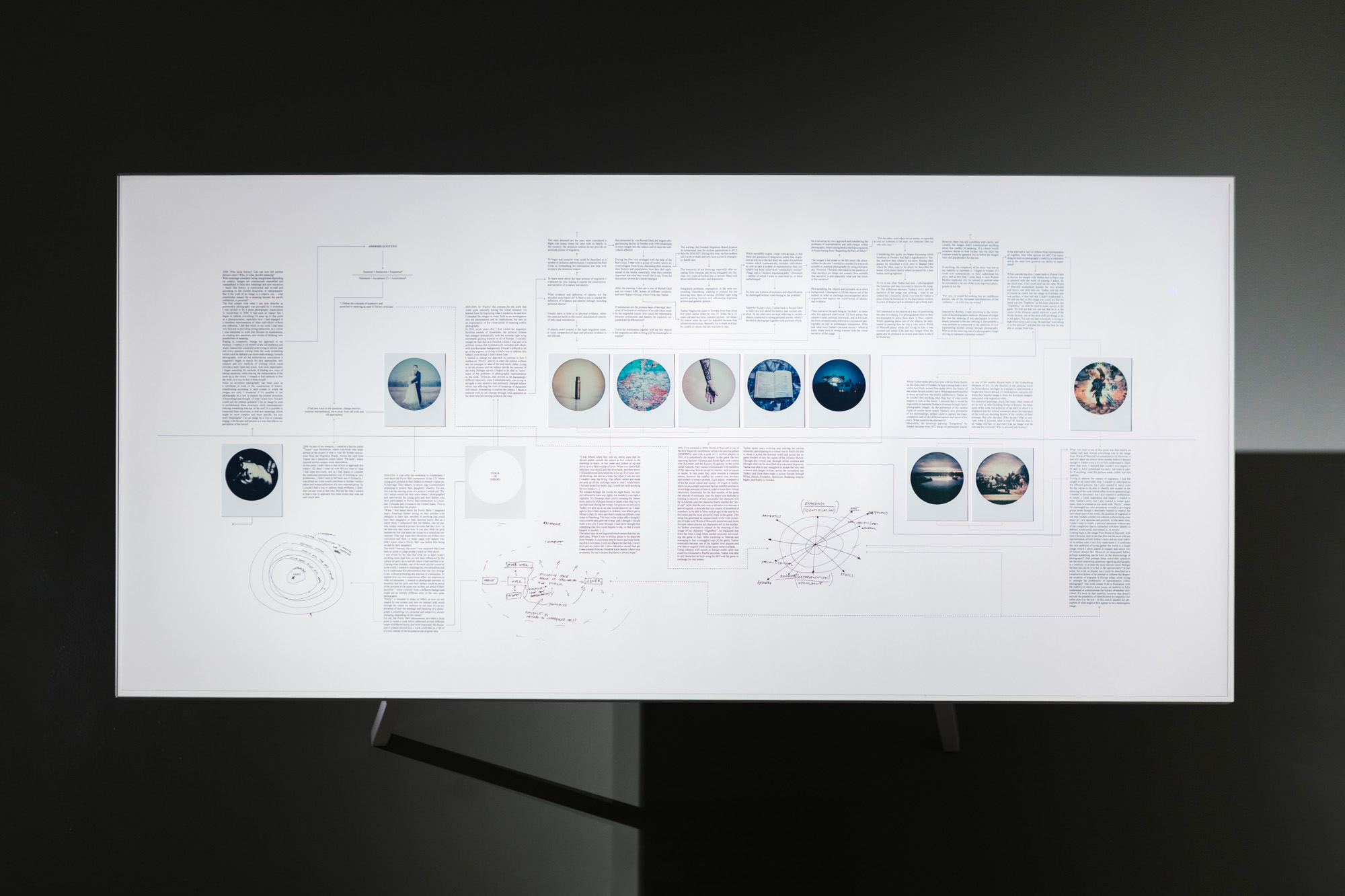

In combination with the image, an audio recording explores Yashar’s story about how the virtual world became a way to escape the real oppression in Iran, both figuratively and literally. The audio continues into present day where Yashar’s asylum application has been rejected six times by the Swedish Migration Agency, leaving him in a legal limbo where he’s neither granted asylum nor can be deported. Meanwhile, a table consisting of texts, notes and Polaroid photographs, investigates the working process and the problems of representation within photography, asking the question if it’s ever possible to tell another person’s story – which in this case is both political and deeply personal.

The work in این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) comes from a frustration with the inability to ever fully understand or communicate the history of another individual. It’s built on that inability – which doesn’t exclude the possibility of identification or empathy – but puts it to the test, in this case to expand the perception of what might at first appear to be a meaningless image. As the virtual world can has a profound effect on what's perceived as the real, it challenges the conventional distinction between reality and fiction in the documentary image. Simultaneously, the scale of the image claims an authority much like a historical painting made to inspire awe at a national museum, and asks: who decides the language of an image? Who is allowed into history?

این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) has been exhibited at Västerbottens Museum, Umeå, Sweden (2022); Noorderlicht International Photo Festival, Heereeven, The Netherlands (2021); Lagos Photo Festival, Lagos, Nigeria (2017); Landskrona Photo Festival, Landskrona, Sweden (2017); and at Galleri Monitor, Gothenburg, Sweden (2017). It was published in the anthology "Young Photography Now – Sweden", Art & Theory (2017), with texts by Niclas Östlind and Annika von Hausswolff.

Installation Views

Installation Views

In Conversation With Annika von Hausswolff

In Conversation With Annika von Hausswolff

این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) could be described as a constructive failure of an attempt to address the desperate situation of migrants in Europe today, while also trying to untangle the problems of representation within photography. The work comes from a frustration with the inability to ever fully understand or communicate the history of another individual. It’s built on that inability, however that doesn’t exclude the possibility of identification or empathy but rather puts it to the test – in this case to expand the perception of what might at first appear to be a meaningless image.

Annika von Hausswolff: Could you elaborate on the conditions and the installation of this work?

David Magnusson: The project consists of three works all revolving around a screenshot from the online roleplaying game World of Warcraft where Yashar Maghsoudi plays as the Blood Elf Paladin ”Nighetboy”, when Yashar was 13 years old and living in Bandar-e Anzali in Iran. By forming a group with other players and traveling for hours across all the virtual borders in world of the game, Yashar had finally been able to make it into the heart of the capital city of the opposing nation. While one of the most difficult achievements in World of Warcraft, Yashar couldn’t realize the full significance of this until two years later. Forced to escape the country after being persecuted by the religious police in Iran, Yashar was able to sell his virtual character to pay for his real escape – most likely saving his life. By participating in a virtual conflict, making it across the borders of a fictional world, it became possible for Yashar to cross the very real borders of Iran and Europe when faced by a real threat.

In combination with the image, an audio recording explores Yashar’s story about how the virtual world became a way for him to escape the real oppression in Iran, both figuratively and literally. The audio continues into present day where Yashar’s asylum application has been rejected six times, leaving him in a legal limbo where he’s neither granted asylum nor can be deported. Together with the audio a table consisting of texts, notes and Polaroid photographs, investigates the creative process and the problems of representation within photography, and asks the question if it’s ever possible to tell another person’s story – which in this case is both political and deeply personal.

AvH: Since I met you a year ago, you been very much immersed in deconstructing everything you had previously learnt about documentary photography. In a way you have been renegotiating all of your former truths, and using that process trying to construct something new?

DM: I think that’s a very good summary of what I have been trying to do. My work is primarily about finding ways to work with photography in a way that explores and examines the medium, but also critiques and problematizes it. If the meaning of a photograph is in constant flux, then I wonder what function a photograph can have beyond the purely aesthetical? By taking my own practice apart and putting it back together in a way where it’s made clear that the result is a reflection, a representation, I hope to explore the actual connection between my work and reality.

AvH: Was there a certain point in time or any specific events connected to when you felt the need to to start this process of deconstruction?

DM: It all started when I had my first contact with post modern photography during the World Press Photo Masterclass in 2008. It showed me that it was possible to use photography to create complex questions rather than to present simplified answers or statements. I was struck by how I could expand on such questions on my own as the viewer of photography made with that approach, conscious of how the meaning was something created in the meeting between me and the work. This realization was something that expanded the possibilities of photography for me and completely changed my approach to the medium.

AvH: Before you started your masters studies you created a project called Purity. It is quite a formal body of work which explores the social phenomenon of the Purity Balls in the United States. If you compare this work to the subject you have been dealing with here and how you have chosen to address it, there is a huge difference in your creative approach and in the function of the final work.

DM: Purity started from the simple idea of trying to create a series of portraits where the participants could be proud of the the pictures and the same way as they are proud of their decisions – while the exact same photograph might hold a very different meaning to a viewer coming from a different context. Even though it's formally reminiscent of classical series of portraits, I hope that the work questions what we consider a portrait and how we interpret it. While Purity of course deals with the interesting phenomenon of the Purity Balls and its participants, the main question I wanted to address was how the meaning of a photograph constantly changes, depending on who's looking at it.

In contrast, my new work in این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) questions what controls the readability – or unreadability – of one single image. In this case it’s a screenshot, which at first sight might appear meaningless, but if you dive into the surrounding works you can learn that the image could be considered as the most accurate summary of the history of an individual. At least the most accurate summary I was able to accomplish. While the image is filled with symbols of a profound meaning for Yashar who's story the project attempts to tell, these symbols only work through his eyes. To decode the image, you are forced to use what you're able to learn of his history from the connected works and try to see the image from his perspective. So while Purity is a portrait series created with the intention to question the stability of the meaning of a photograph, این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) could in a way be considered as the closest thing to a portrait I've ever done.

AvH: Can you speak a little bit about what your initial intentions were for این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass)? Why were you interested in migration as a subject?

DM: The legal system surrounding migration had struck me as such a strange phenomenon as the systems of inclusion and exclusion are principally built on individual testimonials. The interpretation and the credibility that is afforded to these testimonies many times decides a person’s fate, sometimes if they live or die. In turn that creates many questions about who has the right to make such decisions regarding the lives of countless human beings. Researching this process, it was hard not to see similarities in how different testimonials are read differently at different times or in different contexts to how I believe the meaning of a photograph is the result of endless negotiations between different elements of power. In a way I kept coming back to the same questions: who decides history? Who decides how we read knowledge? Who decides what is true?

AvH: So you saw an analogy between how testimonials in migration cases are interpreted and how the meaning of a photograph is read?

DM: Yes, at least a loose one. The only thing I knew was that I wanted to do a project about migration, while simultaneously trying to problematize how history is constructed and how a narrative is interpreted. In contrast to how I worked with Purity, I didn't have any specific concept in mind when I was starting out. I wanted to leave room for the concept to be shaped by the subject during the work process, rather than the other way around, and it turned out to be one of the most difficult things I've ever done. No matter what approach I tried I kept running into different contradictions which made me reject idea after idea. Especially I felt that it was extremely difficult not to fall into clichés or generalizations.

AvH: Parallel to your creation of a portrait of this young refugee, Yashar, you are also creating or recreating yourself as a photographer. Much of این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) is about you reflecting on your position. Could you talk a little bit more about what that process was like for you?

DM: It's interesting what you are saying as much of this process wasn’t premeditated. I started out with a naive ambition about trying to “solve” these problems of representation within photography, which led to a period of intense frustration – or we could call it self reflection. The process was tough but it was also very meaningful to me. As the work is about trying to navigate this impossible maze of ethical issues of photography, which was also what I concretely had been trying to do, I couldn't present the final work without including the process.

AvH: I know that you have been describing the project as a constructive failure. Could you say that, in the midst of this sense of failing, you started to question both the photographic medium and your position as a photographer?

DM: I did. I also started to question the idea of representation itself. I wondered if I could ever even fully understand Yashar's story? And if I couldn’t understand his story, how could I expect to communicate it? That failure of solving that problem became the starting point for what would become the final work, so in that sense it definitely was a constructive one. Suddenly the work transformed from me trying to solve these issues of representation, to me trying to address the difficulties of identifying with the situations of other individuals – while at the same time managing to tell Yashar’s story in a way where I reflect on the difficulties of representing it.

AvH: With all the above said, in what photographic field would you place this work and your own practice at this time?

DM: All my current work comes from that moment in 2008 when I started questioning the notions of realism and representation in documentary photography. In a wider context, I would say that there is a field within art, not necessarily connected only to photography, where there is a profound reflexivity and exploration of what might be described as the documentary.

AvH: Would you call this new journalism or new documentary?

DM: That would be a valid description in one sense, but at the same time it kind of sells it short because I believe that one of the core strengths of this kind of work is that it goes beyond the documentary. It can at once be both a document while it simultaneously critiques the document. It uses mediums such as photography while it consistently critiques the medium employed by reflecting on the instability of the meaning it carries. In the best cases, it forms complex narratives and multilayered works that transcend a traditional documentary or journalistic reading.

AvH: It seems to me like photography itself, photography as phenomenon, promotes both critique and self-reflection. Why do you think that is?

DM: The medium has been promoted as a realistic representation of reality since it’s inception, and that is in direct conflict with how the meaning of a photograph is renegotiated in every single context it is viewed. For me, this conflict makes photography especially interesting as a way to examine reality while simultaneously question the very idea of realism.

AvH: I assume that there could be individuals critiquing the way you are working, as you are blending journalistic or documentary questions with aesthetic ambitions. Some could argue that you should leave the documentary and fully embrace the aesthetical, or the other way around. So why are you deliberately putting yourself in harms way?

DM: In a way this work is a statement towards photography and towards my own background in photojournalism. This complex presentation was from my perspective the most truthful way I could address this subject. I can't exclude the fact that I am a photographer with a position of my own or that the work is the result of my process and my decisions, because they are all key elements in shaping the outcome and therefore need to be part of it. I can't simplify the work either, because I want whoever views it to be able to experience a similar confrontation with themselves and the limits of their perception as I did working through this entire process. That also connects it to what I was trying to achieve in Purity, where I wanted the viewer to get the opportunity to question their own prejudices, as I had needed to do. این نیز بگذرد (This Too Shall Pass) is about the difficulties in understanding another person's story, and in a broader sense connected to the idea of migration. What it really says is that if it’s almost impossible to fully comprehend the depth of the fate of only only single person – then how can we generalize about tens of thousands of human beings in sweeping political discussions, much less vote on who should be able to enter a country or not?